My PhD

Magnesium Chemistry in the Upper Atmosphere of Earth and Mars

This page offers a brief overview of the work undertaken during my PhD - with a focus on modelling and analysis. If you would like to read about my work in further depth, then my thesis and journal publications are available online.

Introduction

The frictional ablation of cosmic dust deposits metals into the upper atmospheres of Earth and Mars. Magnesium is one of the most abundant metals in this cosmic dust and large concentrations have been observed in the Earth’s upper atmosphere. In the terrestrial atmosphere the peak concentration of Mg⁺ ions lie at higher altitudes (90 - 100 km) than the neutral Mg atoms (~89 km). Other metals (Fe, Ca and Na) have been observed using ground-based LIDAR. However magnesium can not be viewed this way as the wavelengths required (280 and 285 nm for Mg⁺ and Mg, respectively) are absorbed by the ozone layer. Therefore, satellite and rocket measurements were utilised to measure the concentrations, altitudes and global densities of the Mg⁺ and Mg layers. A striking difference between magnesium and other meteoric metals is the large ratio between Mg⁺ and Mg - which is even more striking as Mg⁺ is not depleted relative to other metals in the upper atmosphere. This could not be explained by differential ablation, which affects the Ca⁺/Ca ratio. Thus, a difference in chemistry was the likely explanation for this ratio, and will be discussed later.

Experimental

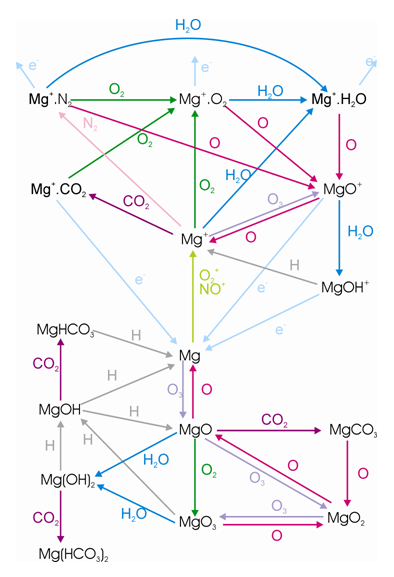

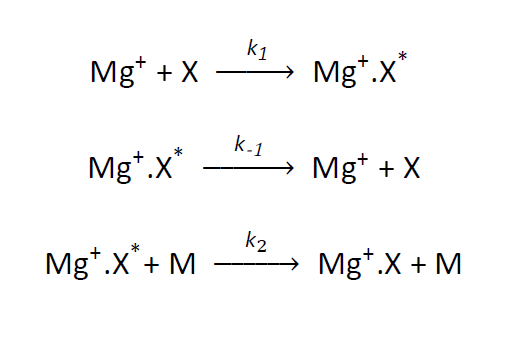

The aim of the experimental systems was to make gas phase kinetic measurements so that rate coefficients could be obtained - to help facilitate the understanding of the chemistry of magnesium in the upper atmosphere. I undertook measurements on many of the reactions shown in the scheme below.

Two experimental systems were utilised; PLP/LIF (pulsed laser photolysis/ laser induced fluorescence) and a fast flow tube. These will not be discussed in detail here, but I gained a vast amount of experience using lasers, pumps, timing instruments, vacuum systems and a mass spectrometer. I will not discuss these systems here, however, detailed experimental setups are available in my publications.

Analysis

### PLP/LIF

The following reactions were studied in the PLP/LIF system:

Mg⁺ + O₃ → MgO⁺ + O₂

Mg⁺ + N₂O → Mg⁺.N₂O

Mg⁺ + X → Mg⁺.X (where X = O₂, CO₂, H₂O and N₂)

Mg⁺ was monitored at an increasing time-delay so that a sufficient decay profile could be built up, as shown below.

[PIC OF DECAY]

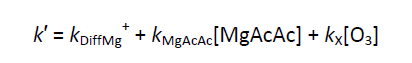

The loss of Mg⁺ ions can be described by the pseudo first-order decay coefficient k′ as, during experiments, the concentration of the reactant and bath gases were kept well in excess of Mg⁺. For reactions with O₃ :

and for the other reactions:

where kₓ is the rate coefficient for the reaction of Mg⁺ ions with the selected reactant; kDiffMg⁺ describes the diffusion of the Mg⁺ ions out of the volume defined by the intersection of the laser beams within the field of view of the detector; kMgX is the rate coefficient for the reaction between Mg⁺ and either the organometallic precursor or any degradation/photolysis products. The value of kDiffMg⁺ + kMgX was determined from a fit of the decay when the concentration of reactant equalled zero. The pseudo first order rate coefficient, k′, was obtained by fitting the experimental decay to a simple single exponential form, A + B_-k′t_ as illustrated by the solid line in the above figure.

### Fast Flow Tube

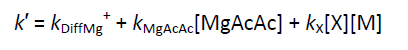

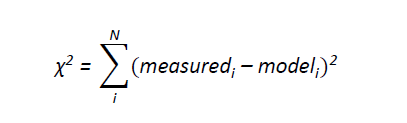

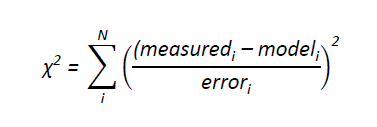

Reactions in the flow tube can be complicated as several reactions and processes are occurring at once. Therefore in order to determine rate coefficients for the reactions studied it was essential to use a numerical model. The model takes into account any gas phase chemistry occurring, diffusion and loss to the walls of Mg⁺/Mg-containing species and, if necessary, any reactants. The changes in concentration down the flow tube of the species of interest were calculated by integrating coupled ordinary differential equations using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta numerical integration scheme. The integration was split into several parts, corresponding to each reaction zone, in which a specific amount of reactants were present. For each reaction zone the reaction time was calculated and the integration was performed over that time. In order to obtain the required rate coefficient, kx, for magnesium ion work the experimental data points were compared with calculated data points to generate a fitting parameter, χ²;

The integrated intensities have no errors associated with them, so a weighted fit was obtained by using the measured value as the weight, i.e. the larger the value, the larger the associated error. If an un-weighted fit was required then the weight was taken to be unity for each point. For magnesium atom χ² was generated using;

where errori is the standard deviation obtained when calculating the average concentration for each data point. Calculations over a range of kx are run, so that a minimum value for χ² could be obtained and therefore an optimal value for kx . The model takes into account the initial conventration of Mg⁺ or Mg. However, these were not experimentally measured, and therefore had to be calculated during the modelling process. The main method resulted in the experimental data being normalised so that the relative concentration of Mg⁺, Mg or magnesium ion species of interest was unity when no reactants were present.

Then, in order to allow the model results to be directly comparable with the experimental results, a scaling procedure was used to find the value for the initial Mg⁺ or Mg concentration, which resulted in a final concentration of unity at the mass spectrometer or LIF detection cell. If this method could not be employed then the initial magnesium concentration had to be included as a second fitting parameter, which required a 2-dimensional minimisation model.

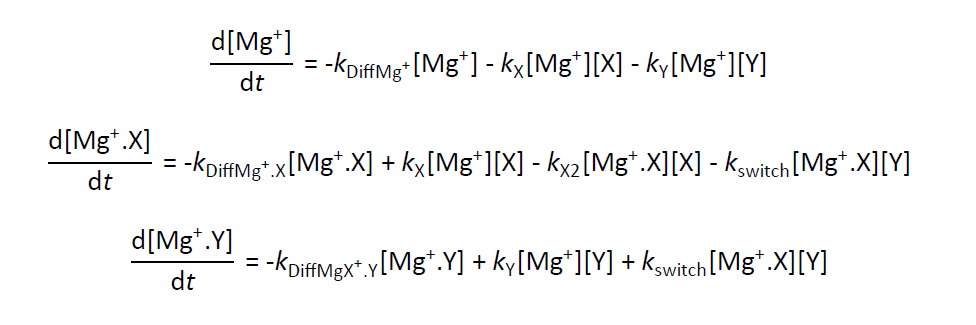

This model was written in Fortran and I worked on updating, improving and modifying the code in order to analyse all of my experimental data. An example of the differential equations solved by the model (for the reaction Mg+.X + Y) are shown below:

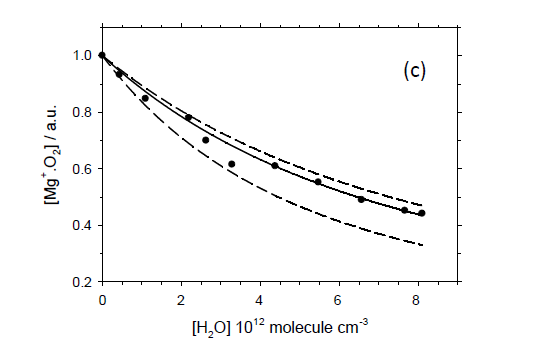

The model output a best-fit to the data (solid line), error margins (dashed lines) and the resulting rate coefficient:

Results

There were a lot of interesting results obtained from my work and I won’t go into all of them here - more, I will touch upon the most interesting points.

Earth’s atmosphere

As mentioned above there is a large Mg+/Mg ratio, that could only be explained by a difference in chemistry, compared to other meteoric metals.

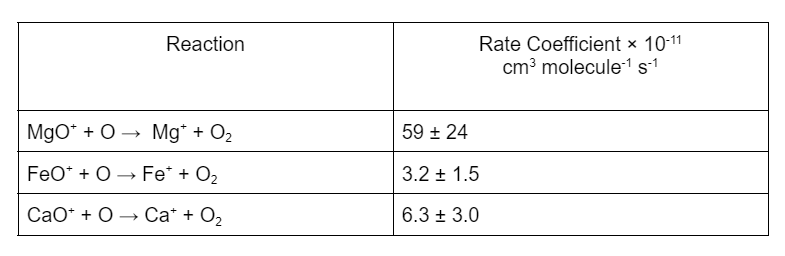

The large ratio of Mg⁺:Mg can be explained by the fast reaction of MgO2+ and MgO+ with atomic O. The rate at which this proceeds is an order of magnitude larger than the analogous reactions of iron and calcium.

This difference allows rapid recycling of Mg⁺-containing ions back to Mg⁺, hence Mg⁺ ions have longer lifetime in the upper atmosphere compared with the other metallic ions. It was also found that the neutral magnesium reservoir species is relatively stable to reaction with atomic H, which leads to efficient removal of Mg atoms from the underside of the Mg layer, which combined with rapid recycling of Mg⁺ ions creates the observed large ion/neutral ratio.

Martian Atmosphere

Like the Earth, other planetary bodies in the solar system are subject to a continuous bombardment of interplanetary dust. Low-lying plasma layers, a few km wide, have been observed in the Martian atmosphere around 90 km. These layers of plasma exist in the aerobreaking region of the Martian atmosphere where meteoroids ablate and it has been proposed that they consist of metallic ions by analogy with the terrestrial atmosphere. These Martian plasma layers resemble sporadic E layers found in the terrestrial atmosphere, which consist mostly of Fe+ and Mg+ ions. However, metallic ions in the CO2-rich Martian atmosphere would be rapidly neutralised by formation of metal-CO2 cluster ions, followed by dissociative electron recombination. During a three-body reaction the third body acts to remove excess energy from the intermediate complex. When Mg+ ions and a reactant, X, collide they form an excited complex, Mg+.X*, which can either dissociate or be stabilised by collision with the third body, M, via the Lindemann mechanism.

This collision with the third body removes the excess energy from the excited complex, thus stabilising it. Generally, the greater the number of internal degrees of freedom a third body possesses the more efficient it will be as energy can be more easily redistributed. The more efficient the removal of energy from the excited complex the faster the rate coefficient is observed to be.

CO2, as a three atom molecule, has a greater number of internal degrees of freedom than He. It will therefore act more efficiently as a third body, and rate coefficients for reactions with CO2 as a third body will be faster than the comparable reaction with He as a third body. Previous models of the Martian sporadic layers have used rate coefficients which do not fully account for the rapid recombination of Fe+ or Mg+ with CO2. The models also do not account for the increased efficiency CO2 has as the third body during recombination reactions. Therefore, the work I undertook aimed to quantify the relative efficiency of CO2 as a third body, compared to He and then combine this with other data to produce a model of the Martian atmosphere to investigate whether the third layer on Mars could consist of metallic ions.

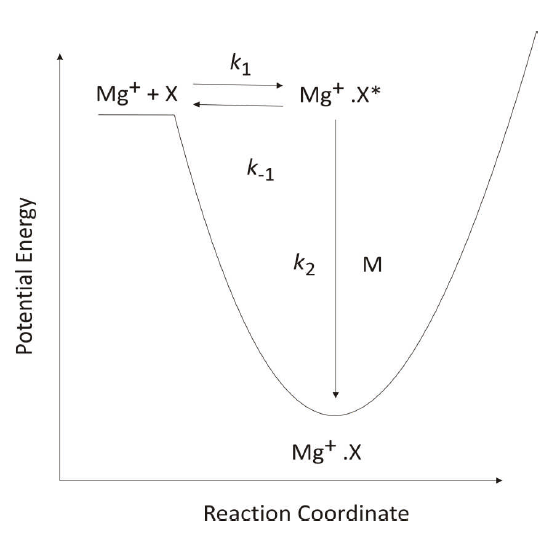

![Plot of k′ versus [CO₂] for recombination of Mg⁺ with CO₂ in the presence of He, at 295 K and 4 Torr. The solid line is a second-order polynomial fit through the data. The dashed line indicates how k′ would vary if He and CO₂ have equal efficiency as the third body.](/Portfolio/images/CO2thirdbody.png)

The following graph shows the efficiency of CO2 as a third body in comparison with He. The dashed line indicates k’ if CO2 had the same third-body efficiency as He. It can be seen that CO2 is considerably more effective, with a final result showing CO2 is 7.7 ± 1.6 more effective than He.

The above work, along with other rate coefficients were input into a 1-dimensional, time-resolved atmospheric model (previously used for modelling the terrestrial atmosphere). The model was used to answer 2 questions; is there a sufficient concentration of ions between 80 - 100 km, that if they were collected by some process into a layer at 90 km, would the resulting concentration exceed that of the measurements; and would the lifetime of the metallic ions in these layers would exceed 20 hours.

The model results showed that Mg+ plays a much more important role than Fe+ in the Martian upper atmosphere. This is because atomic O reacts very rapidly with MgO+ and MgO2+, whereas the analogous Fe reactions proceed at over an order of magnitude slower. The background concentration of Mg+ would therefore be sufficient to form sporadic third layers with a plasma density exceeding 104 cm-3. Also, the chemical lifetime of the layer should easily exceed 10 hours at an altitude of 90 km. Therefore, the results of this work support the theory that the sporadic third layer in the Martian atmosphere is formed by metallic ions produced by meteoric ablation.

This has been a brief foray into my PhD work and if you would like to read more, my journal publications and thesis can be accessed through these links.